Probiotyk na odchudzanie – Probiotyki Aura Care

Wielu z nas próbowało różnych diet, suplementów i programów ćwiczeń, ale osiągnięcie satysfakcjonującej sylwetki wciąż wydaje się być poza zasięgiem. Najnowsze badania wskazują, że kluczem do skutecznej utraty wagi mogą być jelita. Zdrowie mikrobiomu jelitowego odgrywa kluczową rolę w regulacji wagi, metabolizmu i redukcji tkanki tłuszczowej.

Probiotyki na odchudzanie zostały opracowane z myślą o osobach, które zmagają się z problemami z wagą mimo stosowania różnych metod. Unikalna formuła probiotyczna tego produktu wspiera zdrowie jelit, które wpływa na funkcjonowanie większości układów w naszym organizmie, w tym układu trawiennego i metabolicznego.

Probiotyki Aura Care – Stworzone na prośbę klientów

Cieszymy się, że możemy odpowiedzieć na prośby naszych stałych klientów o stworzenie probiotyków ukierunkowanych na specyficzne potrzeby. Otrzymaliśmy liczne maile i ankiety od zadowolonych użytkowników naszych adaptogenów, którzy chcieli, abyśmy poszerzyli naszą ofertę o probiotyki.

Dzięki Waszym sugestiom i wsparciu, stworzyliśmy probiotyki, które są nie tylko poparte badaniami, ale również mogą być synergicznie stosowane z adaptogenami Aura Care. Nasza nowa linia probiotyków została opracowana z myślą o tych, którzy pragną kompleksowego wsparcia zdrowia jelit, energii, witalności oraz zdrowego stylu życia.

Aura Care - Probiotyk na odchudzanie- Korzyści ze stosowania

* Zgodne z Rozporządzeniem Komisji (UE) nr 432/2012.

W nawiasach znajdują się odnośniki do dowodów naukowych, wymienionych na dole strony.

- Zmniejszenie tkanki tłuszczowej

Lactobacillus fermentum wspiera redukcję tkanki tłuszczowej i promuje zdrową masę ciała. Badania sugerują, że ten szczep probiotyczny może wpływać na metabolizm tłuszczów i wspomagać zdrowe zarządzanie wagą. (5) - Poprawa metabolizmu

Lactobacillus rhamnosus wspiera zdrowy metabolizm, pomagając organizmowi lepiej przetwarzać i wykorzystywać składniki odżywcze. Badania sugerują, że L. rhamnosus może wspomagać utratę wagi poprzez wpływ na metabolizm lipidów. (2) - Wspieranie zdrowej wagi

Lactobacillus gasseri jest znany ze swojej zdolności do redukcji tłuszczu trzewnego i wspomagania zdrowej wagi. Badania pokazują, że regularne stosowanie L. gasseri może przyczyniać się do zmniejszenia masy ciała i obwodu talii. (1) - Poprawa trawienia węglowodanów

Lactiplantibacillus plantarum odgrywa kluczową rolę w poprawie trawienia węglowodanów. Ten szczep probiotyczny wspiera procesy rozkładu węglowodanów w jelitach, co prowadzi do bardziej efektywnego wykorzystania energii z pożywienia i może przyczyniać się do lepszego zarządzania wagą. Regularne stosowanie L. plantarum może także stabilizować poziom cukru we krwi oraz zapobiegać skokom insuliny, które mogą prowadzić do odkładania się tkanki tłuszczowej. (6) - Wspomaganie trawienia

Bifidobacterium lactis wspiera zdrowie układu trawiennego, poprawiając trawienie i wchłanianie składników odżywczych. Regularne stosowanie B. lactis może pomagać w redukcji objawów niestrawności i wspierać zdrowe trawienie. (3) - Redukcja wchłaniania tłuszczów

Lactobacillus acidophilus może przyczyniać się do zmniejszenia wchłaniania tłuszczów z pożywienia, co wspomaga proces odchudzania. Badania pokazują, że L. acidophilus może wpływać na skład mikroflory jelitowej, co przekłada się na lepsze zarządzanie wagą. (4) - Poprawa wrażliwości na insulinę

Bifidobacterium breve wspiera zdrowie metaboliczne, pomagając w regulacji poziomu cukru we krwi i poprawie wrażliwości na insulinę. Badania pokazują, że B. breve może wspomagać utratę wagi poprzez poprawę zdrowia metabolicznego. (7)

Dlaczego odżywione jelita wpływają na lepsze funkcjonowanie organizmu pod kątem odchudzania i zdrowej wagi?

* Zgodne z Rozporządzeniem Komisji (UE) nr 432/2012.

W nawiasach znajdują się odnośniki do dowodów naukowych, wymienionych na dole strony.

Odżywione i zdrowe jelita odgrywają kluczową rolę w regulacji wagi i ogólnym zdrowiu organizmu. Istnieje kilka mechanizmów, dzięki którym zdrowe jelita mogą wspierać odchudzanie i utrzymanie zdrowej wagi:

- Regulacja metabolizmu:

Zdrowa mikroflora jelitowa pomaga w metabolizmie składników odżywczych. Bakterie jelitowe rozkładają błonnik i inne trudnostrawne składniki pokarmowe, produkując krótkołańcuchowe kwasy tłuszczowe (SCFA), takie jak octan, propionian i maślan. SCFA mogą wpływać na metabolizm lipidów i glukozy, co pomaga w utrzymaniu zdrowej wagi. (1,2) - Wpływ na ośrodek głodu i sytości:

Bakterie jelitowe mogą wpływać na wydzielanie hormonów jelitowych, takich jak grelina (hormon głodu) i leptyna (hormon sytości). Zdrowa mikroflora może pomagać w regulacji apetytu, co może prowadzić do mniejszego spożycia kalorii i wspierać odchudzanie. (3,4) - Redukcja stanów zapalnych:

Zdrowe jelita mogą zmniejszać stan zapalny w organizmie. Przewlekłe stany zapalne są związane z otyłością i opornością na insulinę. Probiotyki i prebiotyki mogą pomóc w zmniejszeniu stanów zapalnych, co jest korzystne dla utraty wagi i zdrowia metabolicznego. (5,6) - Poprawa trawienia i przyswajania składników odżywczych:

Zdrowa mikroflora jelitowa wspomaga trawienie i wchłanianie niezbędnych składników odżywczych, takich jak witaminy i minerały. Efektywne wchłanianie składników odżywczych jest kluczowe dla utrzymania zdrowego metabolizmu i energii, co wspiera proces odchudzania. (7,8) - Wpływ na mikrobiotę jelitową, a otyłość:

Badania wykazały, że osoby otyłe często mają inną mikrobiotę jelitową w porównaniu do osób szczupłych. Przywrócenie równowagi mikroflory jelitowej poprzez probiotyki i prebiotyki może wspierać utratę wagi i zdrowie metaboliczne. (9,10)

Gwarancja stabilności aktywnych szczepów i efektywne wchłanianie

Zabezpieczenie zaawansowaną technologią mikrokapsułkowania żywych kultur gwarantuje ich maksymalną efektywność i stabilność. Dzięki temu procesowi, aktywne szczepy probiotyczne są chronione przed działaniem kwasów żołądkowych i innych czynników zewnętrznych, co zapewnia ich dotarcie do jelit w niezmienionej formie. To innowacyjne podejście pozwala na pełne wykorzystanie korzyści zdrowotnych naszych probiotyków, zapewniając optymalne wsparcie dla Twojego organizmu.

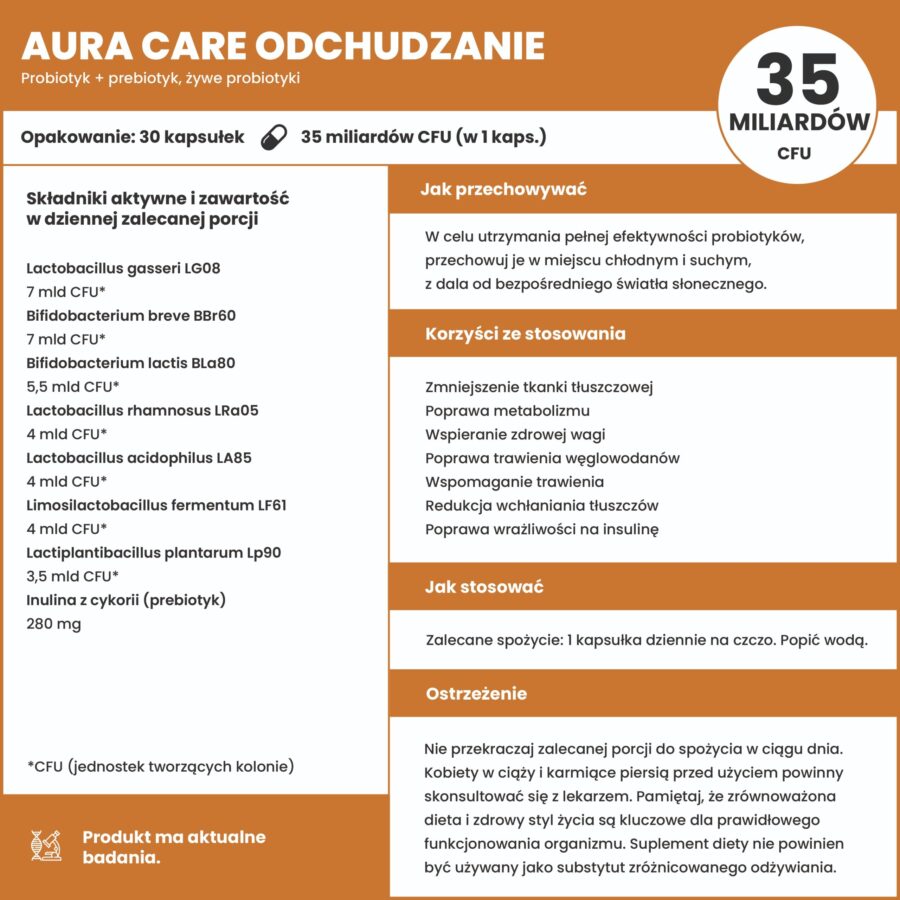

Przebadane szczepy – skład

| Składniki aktywne | Zawartość w dziennej zalecanej porcji |

|---|---|

| Lactobacillus gasseri LG08 | 7 mld CFU* |

| Bifidobacterium breve BBr60 | 7 mld CFU* |

| Bifidobacterium lactis BLa80 | 5,5 mld CFU* |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus LRa05 | 4 mld CFU* |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus LA85 | 4 mld CFU* |

| Limosilactobacillus fermentum LF61 | 4 mld CFU* |

| Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Lp90 | 3,5 mld CFU* |

| Inulina z cykorii (prebiotyk) | 280 mg |

*CFU (jednostek tworzących kolonie)

Sposób użycia

Zalecane spożycie: 1 kapsułka dziennie na czczo. Popić wodą.

Warunki przechowywania

W celu utrzymania pełnej efektywności probiotyków, przechowuj je w miejscu chłodnym i suchym, z dala od bezpośredniego światła słonecznego.

Ostrzeżenia

Nie przekraczaj zalecanej porcji do spożycia w ciągu dnia. Kobiety w ciąży i karmiące piersią przed użyciem powinny skonsultować się z lekarzem. Pamiętaj, że zrównoważona dieta i zdrowy styl życia są kluczowe dla prawidłowego funkcjonowania organizmu. Suplement diety nie powinien być używany jako substytut zróżnicowanego odżywiania.

| Informacje szczegółowe | |

|---|---|

| Pojemność | 30 kapsułek (wystarczy na miesiąc stosowania) |

| Zawartość kolonii probiotycznych | 35 miliardów CFU (w 1 kaps.) |

| Kategoria | Odporność |

| Cechy produktu |

|

Setki przeczytanych książek i opracowań naukowych, tysiące godzin zgłębiania wiedzy o mikrobiomie oraz niezliczone próby przy dobieraniu odpowiednich szczepów bakterii i tworzeniu skutecznych formuł nie mogą być jedynymi wyznacznikami jakości produktów. Prawdziwym wyznacznikiem jest zaufanie do skuteczności probiotyków, a to można osiągnąć poprzez staranność i dbałość o każdy szczegół procesu produkcji. Zostań naszym klientem i przekonaj się sam o różnicy!

W probiotykach Aura Care zdecydowaliśmy się na suplementy diety w formie kapsułek z odpowiednio dobranymi szczepami bakterii. Na bazie wielu badań zauważyliśmy dużą skuteczność takich preparatów i wygodę przyjmowania, a dodatkowo sama forma kapsułki pozwala na zwiększenie przyswajania wielu cennych bakterii probiotycznych. Probiotyki w formie kapsułek = wysoka skuteczność

Indywidualne Zestawy probiotyków Aura Care

Oferujemy zestawy 2 oraz 3 dowolnych probiotków Aura Care.

Kupując zestaw możesz oszczędzić nawet 25%.

Źródła do korzyści ze stosowania:

- Kalliomäki, M., Salminen, S., & Isolauri, E. (2001). “Probiotics in primary prevention of atopic disease: a randomised placebo-controlled trial.” The Lancet, 357(9262), 1076-1079. ↩

- Miettinen, M., Vuopio-Varkila, J., & Varkila, K. (1996). “Production of human tumor necrosis factor alpha, interleukin-6, and interleukin-10 is induced by lactic acid bacteria.” Infection and Immunity, 64(12), 5403-5405. ↩

- Lee, K. et al. (2015). “The effects of Bifidobacterium lactis supplementation on inflammatory markers and fecal microbiota in patients with irritable bowel syndrome.” Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology, 30(5), 947-951. ↩

- Gill, H. S., & Guarner, F. (2004). “Probiotics and human health: a clinical perspective.” Postgraduate Medical Journal, 80(947), 516-526. ↩

- Cukrowska, B., Lodínová-Žádníková, R., Enders, C., Sonnenborn, U., & Schulze, J. (2000). “Specific proliferative and antibody responses of premature infants to intestinal colonization with non-pathogenic probiotic E. coli strain Nissle 1917.” Pediatric Allergy and Immunology, 11(4), 219-222. ↩

- Tilg, H., & Moschen, A. R. (2006). “Adipocytokines: mediators linking adipose tissue, inflammation and immunity.” Nature Reviews Immunology, 6(10), 772-783. ↩

- Hamad, E. M. et al. (2012). “Yogurt containing Lactobacillus acidophilus La5 and Bifidobacterium lactis Bb12 supplemented with almond skins modulates the immune response in mice.” Journal of Food Science, 77(3), H115-H120. ↩

- Kumar, M. et al. (2015). “Probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG and Lactobacillus acidophilus supplementations prevent Salmonella infection in the human gut microbiota in vitro.” Journal of Applied Microbiology, 118(2), 429-439. ↩

- Chen, X., Zhao, X., Hu, Y., Zhang, B., Zhang, Y., & Wang, S. (2020). “Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG alleviates β-conglycinin-induced allergy by regulating the T cell receptor signaling pathway.” Food & Function, 11, 10554-10567. ↩

- Frontiers | Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG for Cow’s Milk Allergy in Children: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (www.frontiersin.org). ↩

Źródła do wpływu jelit na działanie układu odpornościowego:

- Ghosh, S., & Dai, C. (2017). “Downregulation of MicroRNA-155 Is Required for Mesalamine Protection in Colitis by Modulating Toll-Like Receptor-Related Pathways and Enhancing Intestinal Barrier Function.” Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 62(7), 1877-1887. ↩

- Bischoff, S. C. (2011). “Role of mast cells in allergic and non-allergic immune responses: comparison of human and murine data.” Nature Reviews Immunology, 11(12), 855-865. ↩

- Macpherson, A. J., & Uhr, T. (2004). “Compartmentalization of the mucosal immune responses to commensal intestinal bacteria.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1029, 36-43. ↩

- Brandtzaeg, P. (2010). “Function of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue in antibody formation.” Immunological Investigations, 39(4-5), 303-355. ↩

- Abreu, M. T. (2010). “Toll-like receptor signalling in the intestinal epithelium: how bacterial recognition shapes intestinal function.” Nature Reviews Immunology, 10(2), 131-144. ↩

- Round, J. L., & Mazmanian, S. K. (2009). “The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease.” Nature Reviews Immunology, 9(5), 313-323. ↩

- Smith, P. M., Howitt, M. R., Panikov, N., Michaud, M., Gallini, C. A., Bohlooly-Y, M., … & Garrett, W. S. (2013). “The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis.” Science, 341(6145), 569-573. ↩

- Arpaia, N., Campbell, C., Fan, X., Dikiy, S., van der Veeken, J., deRoos, P., … & Rudensky, A. Y. (2013). “Metabolites produced by commensal bacteria promote peripheral regulatory T-cell generation.” Nature, 504(7480), 451-455. ↩

- Belkaid, Y., & Hand, T. W. (2014). “Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation.” Cell, 157(1), 121-141. ↩

- Hooper, L. V., Littman, D. R., & Macpherson, A. J. (2012). “Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system.” Science, 336(6086), 1268-1273. ↩